Space Shuttle Launch Complex 39-B Construction Photos

Page 35

STS-2 on Pad A, Skeleton of Steel, My Desk in the Sheffield Steel Field Trailer

(Original Scan)

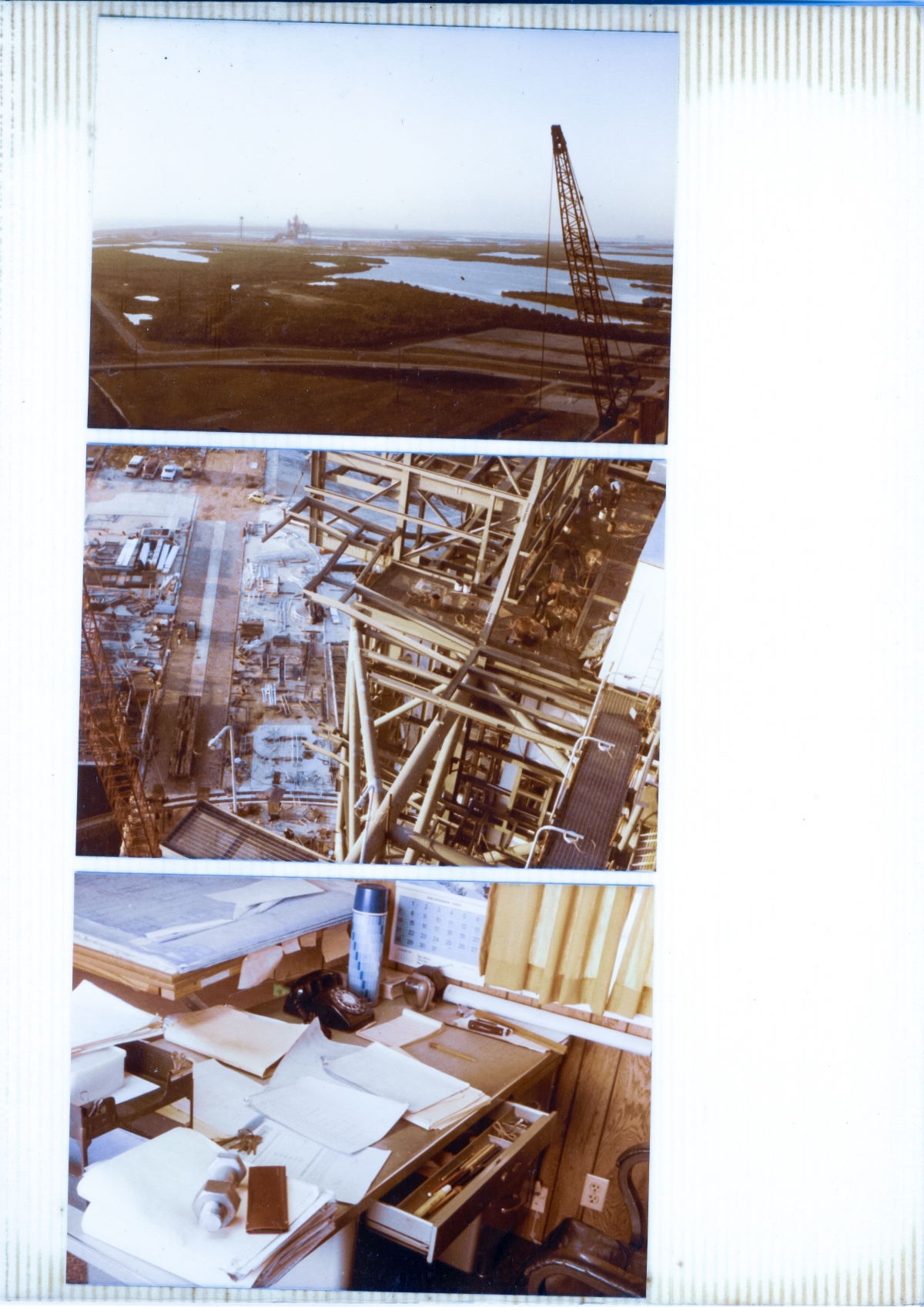

Top: STS-2 rolled out and sitting on Pad 39-A

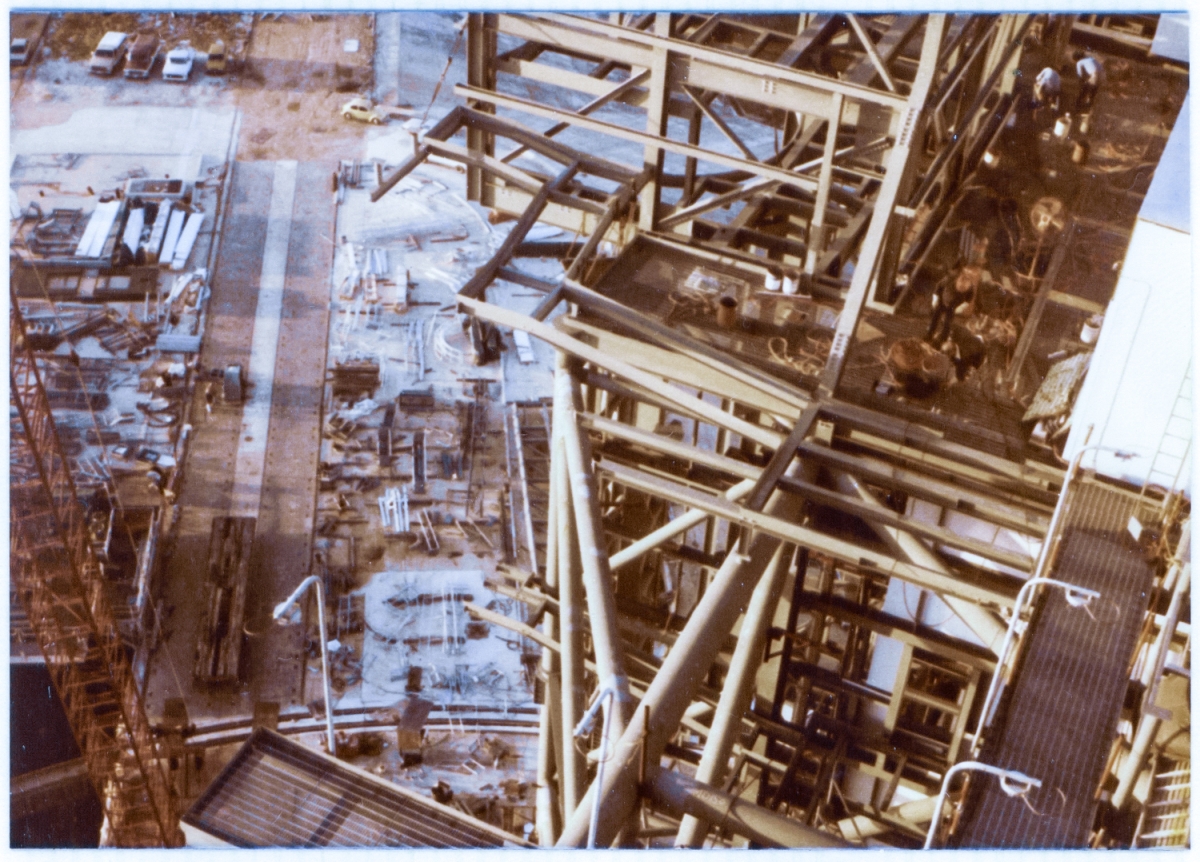

Middle: RCS Room and RSS below, skeletal framing. These are shots I took before I worked at Ivey Steel, when I was working for Sheffield Steel, who was the supplier for the primary structural elements for the RSS. The muscle, the sinew, and the very bones themselves, of a Great Construct, the Rotating Service Structure at Space Shuttle Launch Complex 39-B. A look at the pad deck reveals a lot of steel in the “shake out” area. Trucks would come down from Palatka (which is where Sheffield’s fab shop was) with 25,000 to 50,000 pound loads of all kinds of stuff, and it would be deposited in the shake out area. Part of my job was to take a list of each delivery, and then physically go and locate each piece, and then scratch through it on the list to indicate it was actually delivered. Then I would return to the field trailer, and go find the same pieces on the bill of materials on each of the detail drawings, and highlight them with a yellow highlighter and date them, to indicate the same thing. Then, after each of these pieces was lifted into place and attached to the growing structure, I’d go up on the iron, verify that the pieces were in fact installed, and then go back down to the field trailer with yet another list and then highlight the piece on the erection drawings to indicate that it was up and in place. Now, please go back through these photos and take another look at the welter of beams, columns, diagonals, braces, platforms, handrails, and all the rest of it, and you’ll get an idea of how much work was involved. Every. Single. Piece.

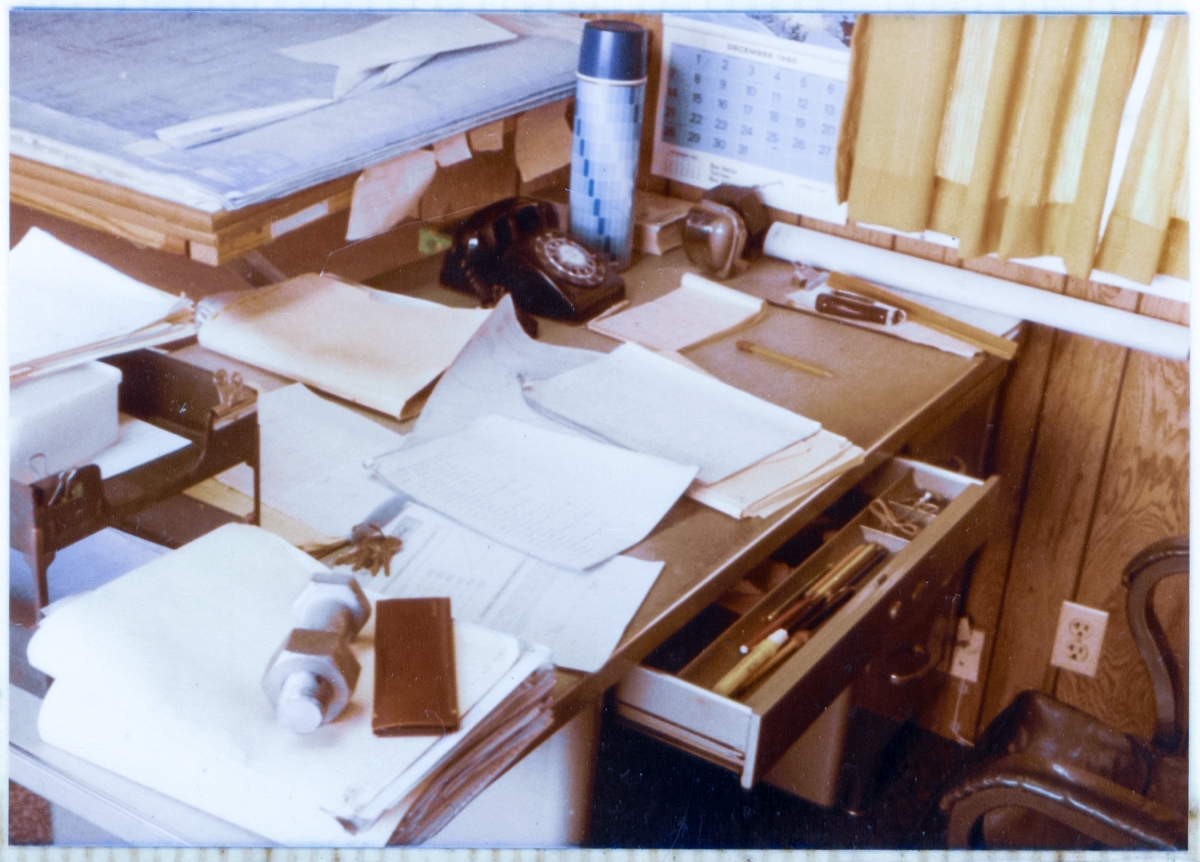

Bottom: My desk in the Sheffield Steel field trailer. This was in the days before there were any pagers or answering machines, and I was originally hired to just sit there like a sack of potatoes and answer the phone whenever my boss, Richard Walls, was out of the trailer.

Sum and total, that was my entire job.

But RW saw that I was interested, and began to hand me things to do, and in a surprisingly short time, with exactly zero by way of previous training for anything even remotely resembling this kind of work, we discovered that I had an innate aptitude for reading structural steel blueprints, and a lot of other stuff, too. And before too long, I was doing things I'd never in my wildest dreams imagined I'd be doing.

Additional commentary below the image.

Top:

(Reduced)

And yet still another one of those views.

It's early morning, and they've just rolled the Space Shuttle Columbia out to Pad A, for only the second time ever.

STS-2 was going to be the first-ever flight of a reused crewed vehicle, and at the time it was a pretty big deal, and an awful lot was going on that had never gone on before, and if you were not there at the time, it's more or less impossible to capture the feeling, but for someone like myself, who was very much into this sort of stuff, it was HUGE.

The Space Shuttle was still very much a brand-new and untested thing, a behemoth, a fire-breathing dragon that just might turn on its masters, and hope and fear mixed together in an indescribable way when simply considering it, and to see it with your own eyes, just down the beach from your own improbable vantage point up on the tower...

Nah. I can't convey this. I need to quit trying. I'm not helping at all with this.

And so, this morning, no doubt in a hurry to get the shot before they rotated the RSS on A Pad around to the mate position, effectively hiding the Shuttle from view, I went up on the tower (most likely the 280' elevation on the FSS, but I cannot prove that), took my little Zeiss Ikon Contessa film camera out, and grabbed this frame.

It may not look like much here, but it was very definitely much, there.

Center:

(Reduced)

They're putting the RCS Room together, and a lot of other stuff, too.

This photo was taken either immediately before, or immediately after the one above it, and if you look close at the crane boom's position against the background, you can see that for the shot of the Shuttle on A Pad, I was farther north on the FSS than I was for this shot, where I'm probably

hanging over the south side of the FSS, near the southeast corner, to get this view looking down toward part of the top truss of the RSS, which defined the roof of the PCR, and upon which the RCS Room, and a lot of other stuff, sat.

Let's wander around through this photograph together for a while, ok?

There's so so very much to see, so very much included, so very much going on, and a casual glance reveals none of it. We spend our lives looking directly at things and we never see any of it.

I oftentimes find myself wondering why a thing like that might be so.

You are leaning (gently now, gently) against the handrail on the south side of things, a single twenty-foot level below the very top of a 250-foot-high steel tower, which itself sits on top of a 50-foot-high artificial concrete hill, which has been constructed on drained swampland near the ocean in East Central Florida.

Your view is down and across, looking almost exactly due south.

Your direction of view as regards the compass can be verified quite easily by taking note of the direction that the crawlerway runs, from top to bottom of the frame, over on the left side of things.

Or at least one-half of the crawlerway, anyway. At the pad, the crawlerway runs exactly north and south, and provides a perfect means for orienting yourself. The other half of it is out of frame, to the far left, on the other side of the darkness of the Flame Trench, the very southernmost end of which occupies the bottom left corner of the frame, running upward for a bit, behind the red latticework of the boom on Wilhoit's big Manitowoc crane, to a point where it intersects the very gentle curve of the top of the Pad Slope, at a place which is obscured in this image by the Engine Service Platform, itself mostly obscured by the boom on the Manitowoc.

To the left of the crane boom, almost at the very bottom of the frame, the curved rail which supported the RSS when it was rotated, can be seen in lighter shade against the dark of the Flame Trench, which was made of refractory bricks, burned slick and black by the exhaust of the Apollo-era rockets which had flown from this pad. On the other side of the crane boom, the curved rail continues on until it is obscured behind the Main Framing of the RSS. The part of the rail that extended out and over the blackened bricks of the Flame Trench was supported in the center by a single very stout support column, which was located in an unfortunate location such that, were you an adventurous sort, and inclined to maybe sneak in there after hours with your skateboard and give it a go, you'd quickly discover that the slope of the trench was so steep that the required switchbacks you'd need to perform to get down it on the skateboard at a speed which would not kill you by hurling you at car-crash speeds into the toe of the Flame Deflector, invariably intersected that damnable support column, no matter how you tried to avoid it. But that, of course, is a different story, for a different day.

Headed south, up and out of the Flame Trench, you can see a lot of material in the shake-out yard, waiting its turn to be picked up by the crane and lifted to its final destination on the tower, where it would be fastened in place by the ironworkers. My tendency was always to tilt in favor of the ironworkers, from the very beginning. These people were performing extremely dangerous work on a daily basis, as if it were no more a serious matter than getting on a bus and heading downtown on it.

It was nothing of the sort.

The strength, bravery, intelligence, and integrity required to be an ironworker is beyond the ability of most people to even imagine, let alone walk out there on high steel and do the actual work.

I will never be able to say enough about the ironworkers.

But I will never stop trying, too.

To the right of the shake-out yard, the growing steel skeleton of the RSS is being added to, in the near-distance.

Coming down into visibility from out of view above the top of the image is the steel framework of the RCS Room. Across from it, up on the roof of the RSS, mostly out of frame, the Hoist Equipment Room has already been framed-out and enclosed in smooth white siding. Between these two structures, the ironworkers have made themselves a temporary work area, and are going about the business of making things happen.

Floats, pneumatic lines, welding leads, bolt cans, a large stand-up fan, and no end of other things can be discerned, along with three ironworkers in this area.

I can't be sure, since this image is only so good and no more, but it looks like the framework for a catwalk is laying on the deckplates next to the Hoist Equipment Room in some state of incomplete assembly, prior to its being lifted by the crane, and swung into place where the connectors will attach it to the rest of the still-growing structure.

Additional catwalk (and access platform) framing can be seen zig-zagging out from main structure of the RSS in the near distance, going over to the near side of the RCS room framing.

Additional catwalks, with steel bar grating installed upon them, can be seen to the left and the right, going out of frame along the bottom edge of the picture.

Notice that the catwalk with grating in place on the left, disappearing out of the bottom of the frame, has no handrails.

The hidden dangers inherent in a place like this are vastly greater than this bland image conveys.

One morning, when I was still fairly new on the job, my boss, Dick Walls, had to restrain one of the ironworkers up near the top of the FSS, to keep him from going down to the pad deck, far below, as ambulances were racing to where his son lay dying after having walked out on a catwalk exactly like these, where the grating had been put in place, but was not yet fastened to the framing it sat upon, and the grating flipped up, underneath him, when he put his weight on it, allowing him to fall through.

That was a very bad day, and I'll never forget it as long as I live.

These people deserve respect.

Bottom:

(Reduced)

My desk in the Sheffield Steel field trailer.

I shall elaborate upon what I've already said, up there above the image.

In the late 1970's I had returned home to Florida after spending four winters on the North Shore of Oahu, riding large waves. I had gotten married (didn't last), and had a child (best son in the world, bar none), but was otherwise more or less drifting, working in the restaurants of a small-time tourist town, with no real plan or program for what I might be doing with my life.

Up at the beach, I used to hang out with a crew of surfers, and one day one of them, Richie Walls, told me his dad worked out on the Cape, needed help, and would I be interested in maybe working for him?

I'm pretty sure I said "Yes," before he was even done asking the question fully. I had no idea who his dad was, or what he might be doing out there on the Cape. A hidden door had suddenly cracked open, and I dove through it without having the faintest idea as to what might be on the other side.

And so it came to pass, on St. Patrick's day, 1980, I found myself in this very trailer for my first day at the new job, a job for which there were apparently no qualifications of any kind required, above and beyond merely being alive and somewhat alert.

I was an answering machine.

That's all. Nothing more was required of me above and beyond my sitting there in that chair, and picking up the handset on that black rotary-dial phone, whenever it rang, if my boss wasn't in the trailer to answer it himself.

Imagine that!

Things have changed, a lot, since then, and for some people it's hard to imagine a time without the pervasive all-encompassing web of communication devices and infrastructure that surrounds and touches everyone, at all times, which presses down imperceptibly, but profoundly, upon us all.

Back in those days, if you wanted to get hold of somebody, you either paid them a personal visit, or you called them up on a phone that was hard-wired to the wall in a room somewhere, and if they weren't in the room, there wasn't any way to reach them, to leave them a message, to do anything at all, except to try again later.

My boss, Dick Walls, was the sole representative for Sheffield Steel at Launch Complex 39-B, and whenever somebody needed to get hold of him, it was usually for a good reason, and it was also usually something that needed to get dealt with NOW, lest it wind up costing somebody a LOT of money, while a clock somewhere kept on ticking.

Answering machines did not exist. No voicemail. No nothing. Just black rotary-dial phones ringing futilely in empty rooms.

The prime contractor on the job got good and sick of that shit pretty quick, and informed Sheffield Steel, the provider of all the iron which the pad was being constructed from, that they had better get somebody in that goddamned field trailer, right now, to pick up the goddamned phone when it rang, and go physically hunt down Dick Walls to deal with whatever emergent problem the phone call represented, or there would be hell to pay.

And so, they needed a warm body to occupy that chair next to the phone.

Impossibly, not one, but two of my surf buddies down at the beach, had been tapped for this job previously, and both of them had flunked out!

Can you imagine being too useless to handle sitting in a chair and answering a phone when it rang?

To literally not qualify for answering a goddamned phone?!?

Impossible!

But true.

And so, The Fates decreed that James MacLaren be the third guy to occupy that chair and answer the goddamned fucking phone when it rang, so as Pat Costello of the Frank Briscoe Corporation would not fly into yet another rage and put more holes in the walls of his own field trailer with his bare fists.

But, unlike his predecessors, James MacLaren was deeply interested in what was going on all around him.

James MacLaren was working on a goddamned Moon Rocket launch pad, right in the middle of getting it ready for what was to follow, getting it ready to launch goddamned Space Shuttles for god's sake, and there was no way any of it was going to get past him if he had anything at all to say about it.

And I guess, in the end, that's what it all comes down to: Are you interested?

Can you bring yourself to become interested?

Can you bring yourself to become interested in something worthy? Something that rises above the endless landscape of banal self-serving entertainments which no end of low-energy people fill all the days of their lives with?

If so, then things will happen.

And if not, then things won't happen.

And holy shit, but did an awful lot of things happen after I sat my skinny little butt down in that chair for the first time!

I had no idea what was coming.

Nor did I care in the slightest.

Just let it come!

And so it did.

Ok, enough of that. A few notes about what's on the desk, perhaps.

Down near the bottom left of the frame, a large hot-dip galvanized bolt with a smooth shank and a matching nut threaded upon it holds down some folders filled to overflowing with paper.

Every desk in a place like this has some trinket or other kicking around on it somewhere.

We were structural steel people, so it would stand to reason that a few outsize structural bolts might be found, and indeed that was the case. This one looks like it's probably a hinge pin for a small folding platform somewhere. Hole for a cotter pin. Smooth shank. Heavy-grade. Matches the description fairly well, but I have no recollection of how it came to wind up in my possession, alas.

Look diagonally across the desk to where the (unattached to anything) pencil sharpener is located below the calendar (which shows December 1980 as the month), and look just behind the pencil sharpener. Up against the wall, is the nut for a much larger bolt, but it's dark, ungalvanized, and pretty nondescript in this image, despite its size.

Back to the near corner of the desk, right next to the galvanized bolt, a dark longish rectangle also rests on top of the folder.

That brown rectangle is the cover for my calculator, which you can just see the end of, inside of it. Back in those days, calculators were still pretty new and marvelous (the business of taking a square root by simply pressing a button still fell more or less under the heading of sorcery back in those days) and this particular calculator, which was given to me by ex-wife number one in the days before the 'ex' appeared, was just about the same size and shape as a slide rule, because people were still unsure that an inscrutable electronic device might really be able to replace one. So the people who made it sought to reassure those who still harbored doubts, by constructing it in the shape of the slide rules that it replaced. Imagine that. I got one hell of a lot of use out of that thing over the years, until I left it on the front seat of my VW Bug where I'd parked it on the pad deck one day, very near to where you see it in the middle image on this page, left of center, up near the top of the frame, and then sat down on it unwittingly and broke it in half. Ah well, so it must be.

Over by the pencil sharpener is a book. My guess is that's a library book. Perhaps something by Alexandr Solzhenitsyn. I was going through all of Solzhenitsyn's stuff back then, and still regard him as my favorite author, and Gulag Archipelago (which this book most definitely is not) remains as my all-time favorite piece of literature, and remains as the one piece of literature which has had the greatest effect upon my life. Over time, I read a lot of books during the hours I had no tasks to perform, and the phone wasn't ringing. My boss was not only fine with that, he actually encouraged it. My taste in reading material is almost exclusively non-fiction, so if I'm reading, I'm learning, and Dick Walls thought that was a good thing.

Next to the book is my thermos for nice cold milk. Up on the in/out tray across the desk on the other side, you can see part of the Tupperware that my ham sandwiches would wait for me in until lunch time. I ate a lot of ham sandwiches back then.

The paperwork and folders is all shipping lists and associated paperwork that's required for keeping track of fabrication, delivery, and erection of all the zillion different pieces of iron it takes to build a launch pad with.

By this time, even though I was still new at the Pad, Dick Walls had come to the realization that I had some kind of weird innate ability to read blueprints. You can see them there on the makeshift drawing table, right behind the black telephone. Hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of big 'F' size blueprints are required on a job of this size. And they were deeply-mysterious and complex pictures of the inner workings of a launch pad. How could I not be fascinated with the damn things? Who the hell gets to pour over drawings of a launch pad and then go out and climb around on the goddamned thing, scuffing their boots on the tens of thousands of pieces of real-world iron which the hundreds of mysterious drawings showed in ink-on-paper? Nobody, that's who. And yet, there I was, sitting in the trailer, smelling the faint aroma of ammonia that came off of the drawings, free as a bird to go through them as much as I might ever want to (which was a lot), trying to figure out what they were. What they meant. How they worked. Oh hell, it was fucking christmas day every day, and I was a goddamned five year old. To this day I do not believe my good fortune to fall unexpectedly into such a place.

We never so much as suspected such a thing when I first showed up to be an answering machine, but I had the ability to look at those blueprints and see things.

Mistakes and inconsistencies, in particular. And I just started out by looking at the damn drawings when I wasn't doing anything (which, with the phone not ringing, was a lot of the time) and asking Dick Walls stuff like "Why is this here?" and he'd go to answer the question (He was a Good Man, hell, he was like a second father to me. I owe so very much of what I've done over the years to him.), and in so doing would discover that I'd caught a mistake somehow. I never set out to make anybody look bad, I just wanted to know why. I'm curious (both definitions, by the way). I've been that way all my life. I'm still that way now, too.

And I would get all excited like a little kid, and say, "Look what I found! Look at this! Look at this!" and sure enough there would be two sets of "78B6 R/L" (or whatever) on the erection drawings instead of only one like the detail drawings showed, and Dick would groan twice, once because it meant that Sheffield had fucked up somehow (hopefully nothing major, hopefully just a draftsman writing the wrong digit in the wrong place), and a second time because I was so damnfool happy that I'd found it.

I cannot describe the exhilaration that came with making discoveries that fucking goddamned rocket scientists out on Cape Fucking Canaveral, had failed to catch. I guess it's going to have to be enough to just say that it felt really good. Made me feel like I was actually doing something.

Regardless of how Richard Walls may have groaned at the time, it was always better to find shit like this in the field trailer than it was to find out up on the tower with a crew of ironworkers and a crane brought to a dead, expensive, halt, while the issue got sorted out satisfactorily, so RW would continue to not only encourage me in my efforts (with admonishments to try and not be so damn pleased with myself for finding stuff), but would also flip new tasks at me and see how I did with them.

Turns out I did pretty damn good with all of it. I was possessed of a multitude of hidden gifts, none of which I had ever been given the slightest clue about in all the previous days of my life. Deeply-hidden gifts. And this has caused me to now believe, whether rightly or wrongly, that everyone is possessed of their own, differing, deeply-hidden gifts which are silently waiting for the Hand of Fate to call upon them, to let their possessors in on the secret that they have been carrying around inside themselves, unknowingly, for a lifetime.

No, I do not know where it comes from. It's just inside of me somewhere, and it's there when I need it, and beyond that I do not have the faintest clue as to how any of it works, or why it would be the least trouble for anybody else to do it. Except that most people can't. Or won't. So I dunno.

I think it all comes back down to interest. If you're interested, if you're really interested, then you'll pick it up pretty damn quick. So I try to be interested in things that matter. Things that make a difference. The things that underpin the world around me. All of that why stuff hidden down there underneath the what stuff that lives up on top of it. I have almost no interest at all in games and entertainments and sports and magic and spooks and religion and who's sleeping with who and who's car is the shiniest and who's house is the biggest and all the rest of that awful goddamned crap. That stuff doesn't do anything except move people around in endless, pointless, useless circles. It's all just for show. Bores me to tears. Give me something with a little substance to it. Please. Give me something I can sink my teeth into.

Return to 16streets.comACRONYMS LOOK-UP PAGEMaybe try to email me? |